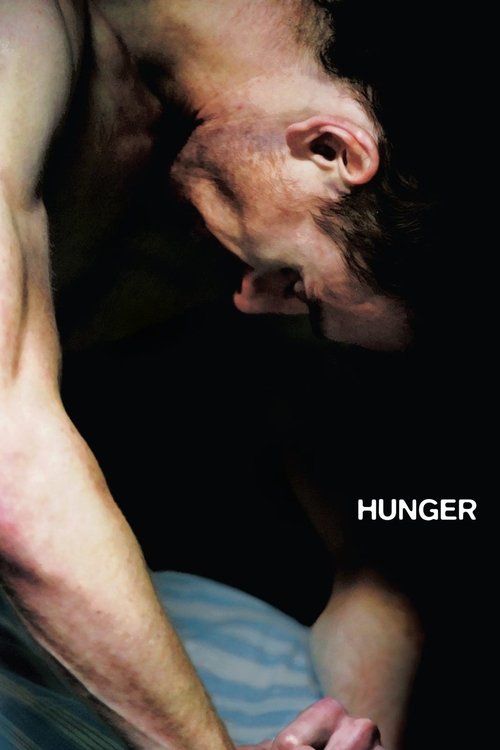

Title: Hunger

Year: 2008

Director: Steve McQueen

Writer: Steve McQueen

Cast: Michael Fassbender (Bobby Sands),

Stuart Graham (Ray Lohan),

Liam Cunningham (Priest),

Helena Bereen (Raymond's Mother),

Laine Megaw (Raymond's Wife),

Runtime: 96 min.

Synopsis: The story of Bobby Sands, the IRA member who led the 1981 hunger strike during The Troubles in which Irish Republican prisoners tried to win political status.

Rating: 7.246/10

The Body as Battleground: Hunger’s Visceral Cry for Humanity

/10

Posted on July 13, 2025

Steve McQueen’s Hunger (2008) is a cinematic gut-punch, a film that wields the human body as both weapon and canvas to explore the limits of resistance and the cost of conviction. Centering on Bobby Sands’ 1981 hunger strike in Northern Ireland’s Maze Prison, McQueen’s directorial debut is less a historical recounting than a visceral meditation on suffering, dignity, and the collision of ideology with flesh. The film’s power lies in its unflinching focus on physicality through Michael Fassbender’s harrowing performance and Sean Bobbitt’s stark cinematography while its narrative restraint invites reflection without preaching.

Fassbender’s portrayal of Sands is a masterclass in embodied acting. His gaunt frame, increasingly skeletal as the strike progresses, becomes a text of defiance, each protruding rib a testament to his resolve. Yet, Fassbender avoids sanctifying Sands; his performance is raw, human, marked by fleeting moments of vulnerability a trembling lip, a distant gaze that ground the character’s martyrdom in relatable fragility. McQueen’s direction amplifies this, using long, unbroken takes to immerse viewers in the prison’s claustrophobic brutality. A 17-minute dialogue scene between Sands and a priest (Liam Cunningham) is a standout, its rapid-fire exchange of moral and political arguments unfolding like a verbal duel, revealing the intellectual stakes of Sands’ choice without resolving them.

Bobbitt’s cinematography is equally uncompromising. The camera lingers on the grotesque urine-soaked corridors, festering wounds, excrement-smeared walls with a painterly precision that finds perverse beauty in decay. This aesthetic choice risks alienating viewers, yet it serves the film’s thesis: the body, in extremis, becomes a site of protest and poetry. Enda Walsh’s screenplay, co-written with McQueen, is sparse but deliberate, prioritizing silence and gesture over exposition. This minimalism, while evocative, occasionally leaves the broader political context opaque, which may frustrate viewers unfamiliar with the Troubles. The film assumes knowledge of the IRA’s struggle, and while this lends authenticity, it risks distancing those seeking a clearer historical frame.

The sound design sparse, haunting, punctuated by clanging cell doors and muffled cries complements the visuals, creating a sensory prison that envelops the audience. If Hunger falters, it’s in its occasional indulgence in aestheticizing suffering, where the line between art and exploitation blurs. Yet, McQueen’s refusal to sentimentalize or vilify any side elevates the film above mere polemic. Hunger is a brutal, beautiful inquiry into what it means to sacrifice the self for a cause, leaving viewers both shaken and contemplative.

0

0