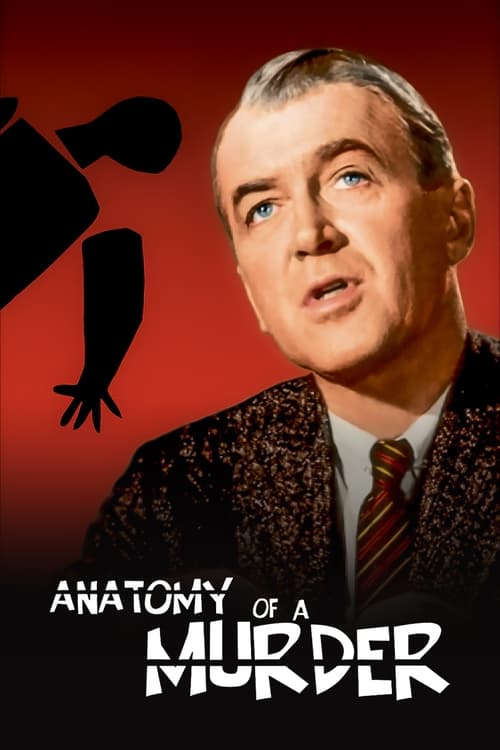

Title: Anatomy of a Murder

Year: 1959

Director: Otto Preminger

Writer: Wendell Mayes

Cast: James Stewart (Paul Biegler), Lee Remick (Laura Manion), Ben Gazzara (Lt. Frederick Manion), Arthur O'Connell (Parnell Emmett McCarthy), Eve Arden (Maida Rutledge),

Runtime: 161 min.

Synopsis: Semi-retired Michigan lawyer Paul Biegler takes the case of Army Lt. Manion, who murdered a local innkeeper after his wife claimed that he raped her. Over the course of an extensive trial, Biegler parries with District Attorney Lodwick and out-of-town prosecutor Claude Dancer to set his client free, but his case rests on the victim's mysterious business partner, who's hiding a dark secret.

Rating: 7.8/10