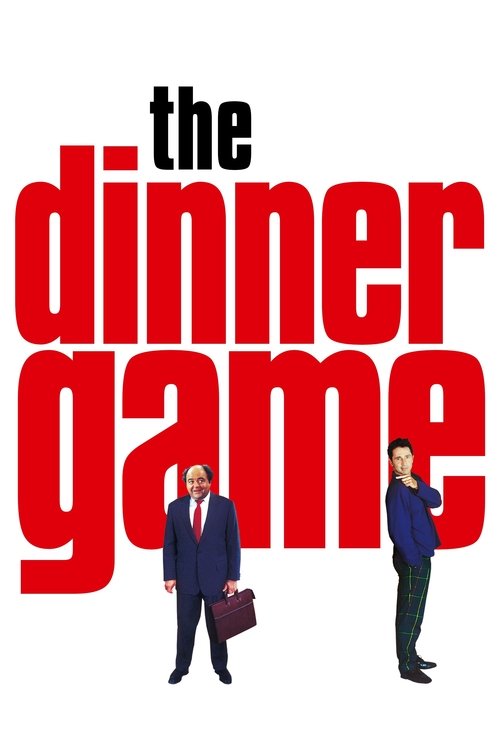

Title: The Dinner Game

Year: 1998

Director: Francis Veber

Writer: Francis Veber

Cast: Jacques Villeret (François Pignon), Thierry Lhermitte (Pierre Brochant), Francis Huster (Juste Leblanc), Daniel Prévost (Lucien Cheval), Alexandra Vandernoot (Christine Brochant),

Runtime: 80 min.

Synopsis: For Pierre Brochant and his friends, Wednesday is “Idiots' Day”. The idea is simple: each person has to bring along an idiot. The one who brings the most spectacular idiot wins the prize. Tonight, Brochant is ecstatic. He has found a gem. The ultimate idiot, “A world champion idiot!”. What Brochant doesn’t know is that Pignon is a real jinx, a past master in the art of bringing on catastrophes...

Rating: 7.772/10