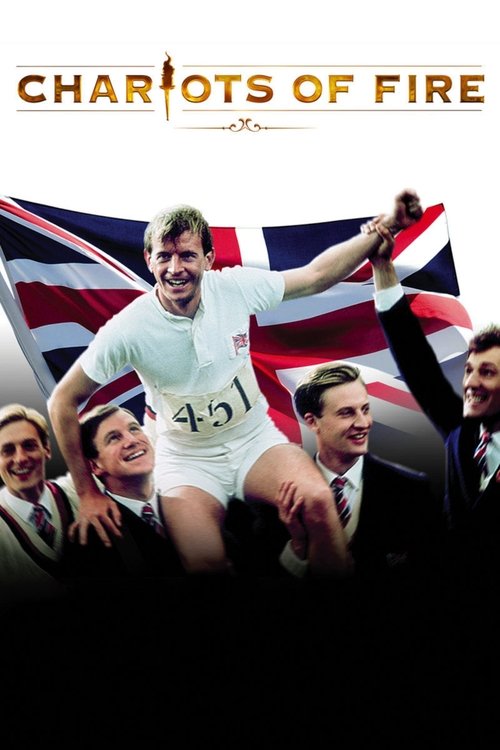

Title: Chariots of Fire

Year: 1981

Director: Hugh Hudson

Writer: Colin Welland

Cast: Ben Cross (Harold Abrahams), Ian Charleson (Eric Liddell), Cheryl Campbell (Jennie Liddell), Alice Krige (Sybil Gordon), Nigel Havers (Lord Andrew Lindsay),

Runtime: 123 min.

Synopsis: In the class-obsessed and religiously divided UK of the early 1920s, two determined young runners train for the 1924 Paris Olympics. Eric Liddell, a devout Christian born to Scottish missionaries in China, sees running as part of his worship of God's glory and refuses to train or compete on the Sabbath. Harold Abrahams overcomes anti-Semitism and class bias, but neglects his beloved sweetheart in his single-minded quest.

Rating: 6.788/10